A 29-year-old woman, G2P1, at 36 weeks of gestation, presents to the obstetric emergency unit with sudden-onset vaginal bleeding. Her prior caesarean delivery raises concern for abnormal placentation, and irregular prenatal care with lack of detailed placental mapping places placenta previa, placenta accreta spectrum (PAS), and placental abruption all in the differential. Each condition poses a high risk for preterm labor, severe maternal hemorrhage, hypovolemic shock, fetal compromise, and stillbirth.

Role of CADAVIZ in understanding the three major third-trimester obstetric emergencies

At the heart of third-trimester obstetric emergencies lies the placenta, whose anatomy, implantation site, and spatial relationships with the uterus and cervix are critical for accurate diagnosis and management. However, studying the human placenta remains inherently challenging. Didactic lectures, textbooks, and imaging often fail to capture its three-dimensional complexity. CADAVIZ offers an immersive, interactive platform that allows users to visualize placental anatomy, trace its development from implantation to maturity, and explore scenarios such as placenta previa, placental abruption, and placenta accreta spectrum. This interactive approach deepens understanding, links anatomy with clinical and imaging findings, and supports informed decision-making during high-risk pregnancies.

Returning to our 29-year-old patient at 36 weeks of gestation, despite the absence of detailed placental mapping, her presentation strongly suggested placenta previa. Two clinical observations supported this. First, her vaginal bleeding was painless; she reported no abdominal discomfort or cramping, and on examination, her uterus was soft and non-tender. Second, the blood was bright red, a hallmark of placenta previa, distinguishing it from the darker, clotted blood often seen in placental abruption.

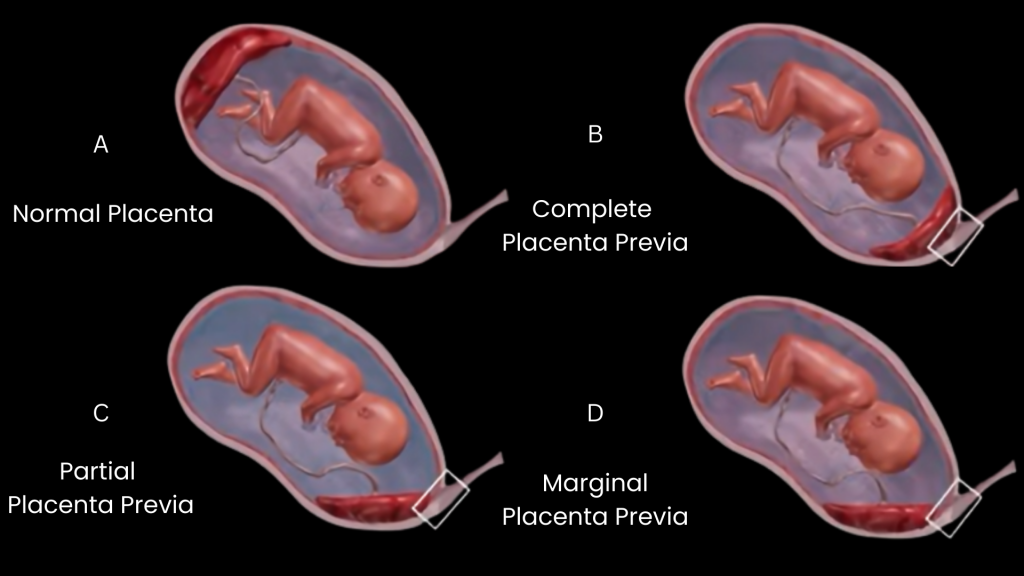

In roughly 0.5–2% of pregnancies, especially in women who’ve had a prior cesarean delivery, multiple pregnancies, advanced maternal age, or a history of uterine surgery, the placenta implants low in the uterus, partially or completely covering the cervical opening. Depending on the extent of coverage, placenta previa is classified as complete, partial, marginal, or low-lying.

Complications in placenta previa typically arise in the third trimester, coinciding with the formation of the lower uterine segment and the beginning of cervical effacement and dilation, either spontaneously or in preparation for labor. As this poorly contractile lower part of the uterus stretches and thins, the placenta, anchored to it, separates without labor, causing sudden bleeding, without pain. The condition can become life-threatening if the bleeding is heavy or recurrent, placing the mother at risk of hemorrhage, anemia, or shock, and potentially compromising fetal oxygenation.

Management focuses on preventing antepartum haemorrhage and optimizing the timing of delivery. This includes pelvic rest, avoiding digital vaginal examinations, and administering antenatal corticosteroids if preterm birth is anticipated. Major cases typically require a planned cesarean delivery, usually around 36–37 weeks.

In placenta previa, early detection is key to a safe outcome; therefore, complete placental mapping should be included in routine second-trimester scans, allowing timely management to reduce maternal complications and improve neonatal outcomes.

Placenta Accreta Spectrum (PAS)

While placenta previa was the primary concern in this patient, the absence of prior placental mapping and painless vaginal bleeding also raised the possibility of Placenta Accreta Spectrum (PAS), in which the placenta abnormally adheres to or invades the myometrium. This occurs mostly due to a deficient decidua basalis, scar tissue remnant of prior cesarean delivery, multiparity, and/or uterine surgery. PAS may manifest as placenta accreta, where the placenta attaches directly to the myometrium; placenta increta, where it invades into the myometrium; and placenta percreta, where placenta penetrates through the uterine wall, sometimes reaching the surrounding organs.

PAS may be clinically silent until delivery or mimic placenta previa with painless bleeding, usually closer to term. Mild abdominal or back discomfort can occur but is uncommon. Complications in placental separation at delivery, can lead to life-threatening consequences such as massive hemorrhage, uterine rupture, and invasion into adjacent organs.

Management of PAS necessitates early detection so that multidisciplinary planning, imaging-guided strategies, and planned delivery can prevent hemorrhage, reduce maternal morbidity, and optimize neonatal outcomes.

Placental Abruption

The third major obstetric emergency of the third trimester is placental abruption. Unlike placenta previa, which causes painless bleeding due to abnormal placental location, placental abruption involves premature separation of a normally implanted placenta. Placental abruption is classified based on the extent of placental separation. Partial abruption involves detachment of only a portion of the placenta, with fetal compromise depending on the size of the separation. Complete abruption involves detachment of the entire placenta, often leading to severe fetal distress or demise. Bleeding can be revealed, with visible vaginal blood, or concealed, trapped behind the placenta, potentially causing severe hemorrhage despite minimal external bleeding.

Clinically, abruption typically presents with sudden-onset abdominal or back pain, uterine tenderness and rigidity, vaginal bleeding (which may be absent in concealed cases), and reduced fetal movements in moderate to severe cases. Life-threatening complications include massive maternal hemorrhage, disseminated intravascular coagulation due to placental tissue thromboplastin, acute fetal hypoxia from loss of perfusion, preterm labor, or uterine rupture.

Because bleeding can be concealed, maternal shock may develop rapidly, requiring prompt recognition, rapid assessment, and immediate multidisciplinary management, including close monitoring, corticosteroids, blood transfusion, and timely delivery—often by cesarean—to optimize maternal and fetal outcomes.

Preventing Third-Trimester Obstetric Emergencies

Routine second-trimester anatomy scans, performed between 18 and 22 weeks, with detailed mapping of placental location, depth of invasion, and proximity to the cervical os enables clinicians to anticipate complications of abnormal placentation (placenta previa, PAS and placental abruption) and plan the timing and mode of delivery. Low-lying placentas should be reassessed in the third trimester, as many move upward with uterine growth.

When to Seek Immediate Medical Attention

Pregnant women should seek urgent care if they experience danger signs such as sudden or heavy vaginal bleeding, severe abdominal pain, persistent headache, blurred vision, or reduced fetal movement. As obstetric emergencies can develop rapidly and unpredictably, prompt medical attention can prevent life-threatening complications for both mother and fetus.

Writer – Dr. Debashree Das

Sr. Medical Content Writer